|

| Home | | About Us | | Water Planning | |

Groundwater | |

Conservation | |

Environmental Flows | |

Drought Mgmt. | |

Resources | |

Search | | ||

|

Special Topic: Interconnectivity  The interconnectivity of surface and ground water supplies is well documented and understood. However, Texas water law generally fails to adequately recognize this concept, and the state's planning and management strategies frequently treat ground water and surface water separately.

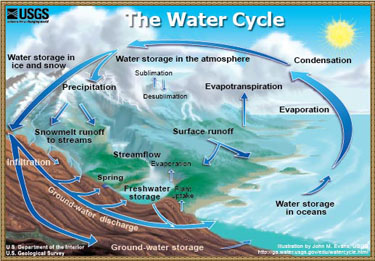

The interconnectivity of surface and ground water supplies is well documented and understood. However, Texas water law generally fails to adequately recognize this concept, and the state's planning and management strategies frequently treat ground water and surface water separately.Given the increasing pressure on Texas water supplies, it is time for key water planning processes, including recent systems for surface water and ground water planning and management and the new environmental flow process to better account for interconnectivity. Topics  What is Interconnectivity? What is Interconnectivity? Examples of Interconnectivity Examples of Interconnectivity Policy and Science of Interconnectivity Policy and Science of Interconnectivity Incorporating Interconnectivity into Planning Incorporating Interconnectivity into PlanningWhat is Interconnectivity? The water cycle, which includes both surface and groundwater, is a dynamic and interconnected system. In many instances, surface water, which includes water flowing through our creeks, streams, and rivers, has its origins below the surface, just as the water stored in the major and minor aquifers below the ground has flowed or percolated downward from the land's surface at some point in the past. More research is needed across the state to completely understand the degree of interconnectivity of our water resources. However, in some areas, the fact that our surface water resources are highly dependent on the underlying aquifers (and vice versa) is well understood and documented. EXAMPLES OF INTERCONNECTIVITY  The Hill Country and Texas Plateau

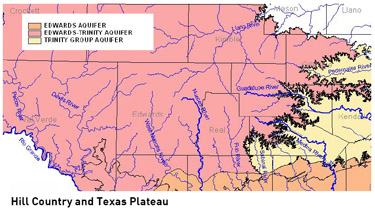

The Hill Country and Texas Plateau The influence of springflow on creeks and rivers is strongly evident in the Hill Country and the Texas Plateau, where groundwater pours out of the Edwards-Trinity (Plateau) Aquifer through springs to form the headwaters of the Pecos, the Devils, the Nueces, the Frio, the Sabinal, the Medina, and Guadalupe, the Llano, and the San Saba Rivers. Springs and other natural discharges (1) of the Trinity Group Aquifer continue to support most of these rivers as they flow east and southeastward across central Texas towards the coast. Natural discharges of the Trinity Group Aquifer also form the headwaters of the Pedernales and Blanco Rivers. Especially during periods of low rainfall and minimal surface runoff, springflow from the underlying aquifers is the life support in maintaining surface flows - like rivers - throughout the state. For example, springflow from the Edwards Aquifer in Hays and Comal Counties becomes almost the sole source of downstream water flows in the Guadalupe River during droughts. 2006 was a very dry year for most of Texas. On September 5, 2006, springflows from Comal and San Marcos springs accounted for 86% of the flows of the Guadalupe River at Victoria. (2) Farther west, up on the Edwards Plateau, stream flow data collected by USGS during the summer of 2006 show that the flow of the spring-fed Llano River accounted for approximately 75% of the water flowing into the Highland Lakes.(3) The Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer and the Brazos River The United States Geological Survey conducted a gain-loss study and an analysis of historical streamflow measurements for the Brazos River reach from McLennan County down through Fort Bend County. Based on both the current study and the historical data, there is an appreciable increase in flows of the Brazos River as it trends southeast across the Falls County line towards the city of Bryan. Underlying that reach and supporting the flows of the Brazos are the Carrizo-Wilcox, Queen City, Sparta, and Yegua-Jackson Aquifers.(4) From the measurements collected in 2006, a section of the river traversing the Yegua-Jackson Aquifer outcrop (5) gained 258 cubic feet per second (cfs) in March, which accounted for approximately 30% of the measured river flow at that location. In August, another section flowing over the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer outcrop gained over 194 cfs, accounting for approximately 33% of the total flows.  The Canadian River and the Ogallala Aquifer

The Canadian River and the Ogallala AquiferNatural discharges from the Northern Ogallala Aquifer support the flows of the Canadian River as it traverses the Texas Panhandle. In the eastern portion of the Texas Panhandle where the Ogallala Aquifer has not been excessively dewatered, it also discharges to a variety of smaller streams and rivers within the Canadian River Basin. In Hemphill County, for example, numerous tributaries to the Canadian River, including the Washita River, Red Deer Creek, and Gageby Creek among others, all reportedly flow continuously even through drought periods due to natural discharges from the Ogallala Aquifer. The Hemphill County Groundwater Conservation District (GCD) is presently collecting over 250 county-wide synoptic (6) groundwater levels to help define how high the groundwater level in the Ogallala Aquifer must remain in order for the aquifer to continue to discharge to local creeks and rivers. Future studies may include compiling stream gaging datasets to help determine the impact groundwater levels in the Ogallala have on local streamflows. SCIENCE AND POLICY OF INTERCONNECTIVITY While two separate legal regimes regulate the management and use of groundwater and surface water, there is some recognition in the Texas Water Code (7) that the use and availability of one resource affects the other. For instance, the TCEQ is required to consider the effects of granting a surface water permit on groundwater and groundwater recharge. (8) In turn, groundwater districts are required to consider if the "... proposed use of water unreasonably affects existing groundwater and surface water resources ..." when evaluating groundwater permit applications.(9) Groundwater districts must also coordinate with surface water management entities when developing their management plans. (10) When evaluating surface water availability in the surface water permit process and groundwater availability in terms of aquifer conditions, computer models are used to simulate resource distribution and availability. To a certain degree, both the Groundwater Availability Models (GAMs) and surface Water Availability Models (WAMS) have the technical capacity to factor in flows from one resource to the other. However, the degree of accuracy of the data used varies and the effort that is undertaken to adequately portray the interdependency of the resources within the modeling efforts is not standard, required, or even guaranteed. A report prepared for the TWDB, by an outside engineering firm about linking the surface and groundwater models concluded that "... a consistent approach and procedure is needed to represent streamflow gains and losses in the WAMs and GAMs." (11) Some of the specific recommendations included:

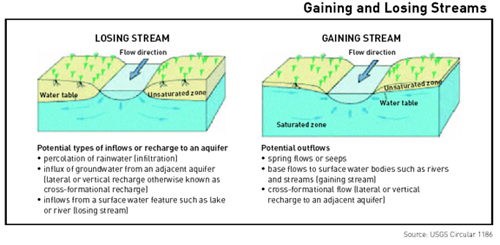

Gain-Loss Studies Information about the relationship between rivers and creeks and the underlying aquifers can be assembled through gain-loss studies. The goal of a gain-loss study is to identify the segments of the rivers which gain water from the underlying aquifers (termed gaining) and which segments lose water to the underlying aquifer (losing). This is achieved by measuring the volume of water that is flowing in the river at strategic locations throughout the watershed. These volumes are then compared to see where the volume has increased (indication of a gaining segment and potential springflows) or decreased (indication of a losing segment or recharging of the aquifer).  The U.S. Geological Service (USGS) has been conducting gain-loss studies across the state since the early 1900's. According to an assessment of those studies conducted by the Bureau of Economic Geology in 2005, most large streams in Texas gain, rather than lose, water during low-flow conditions (climatically dry when there is little surface runoff).(13) In fact, the assessment concluded that groundwater discharges from underlying aquifers dominates river flows throughout most of Texas during these times.(14) Incorporating Interconnectivity into Planning Given the interconnectivity of surface and groundwater resources in many areas of Texas, it is unrealistic to think that we can sustainably manage and regulate one resource in isolation from the other. While certain elements of the current law provide an opportunity for more integrated management, much more is required to ensure those opportunities are realized, including:

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||